Part 1 | The First Rotating Bezel: The Men, Their Myth, and Their Watches

Within the watch world, companies are always quick to recount their milestones and marks on watchmaking history…

1800 – First tourbillon (Breguet)

1926 – First self-winding wristwatch (Fortis’ Harwood Automatic)

1932 – First Dive wristwatch – (Omega Marine)

1953 – First GMT-hand watch – (Glycine Airman)…

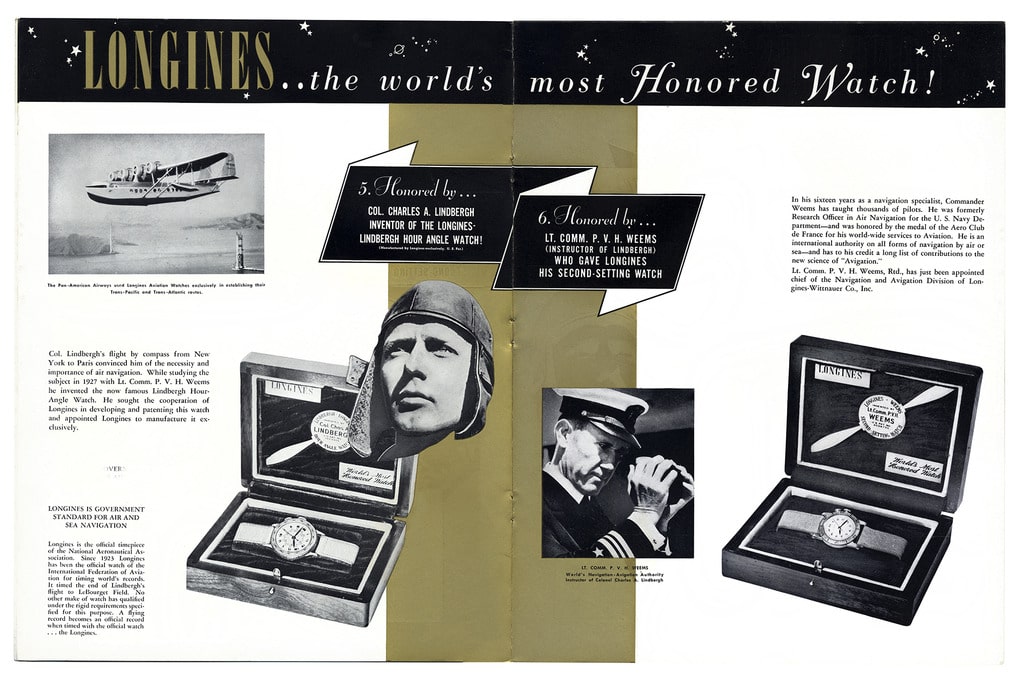

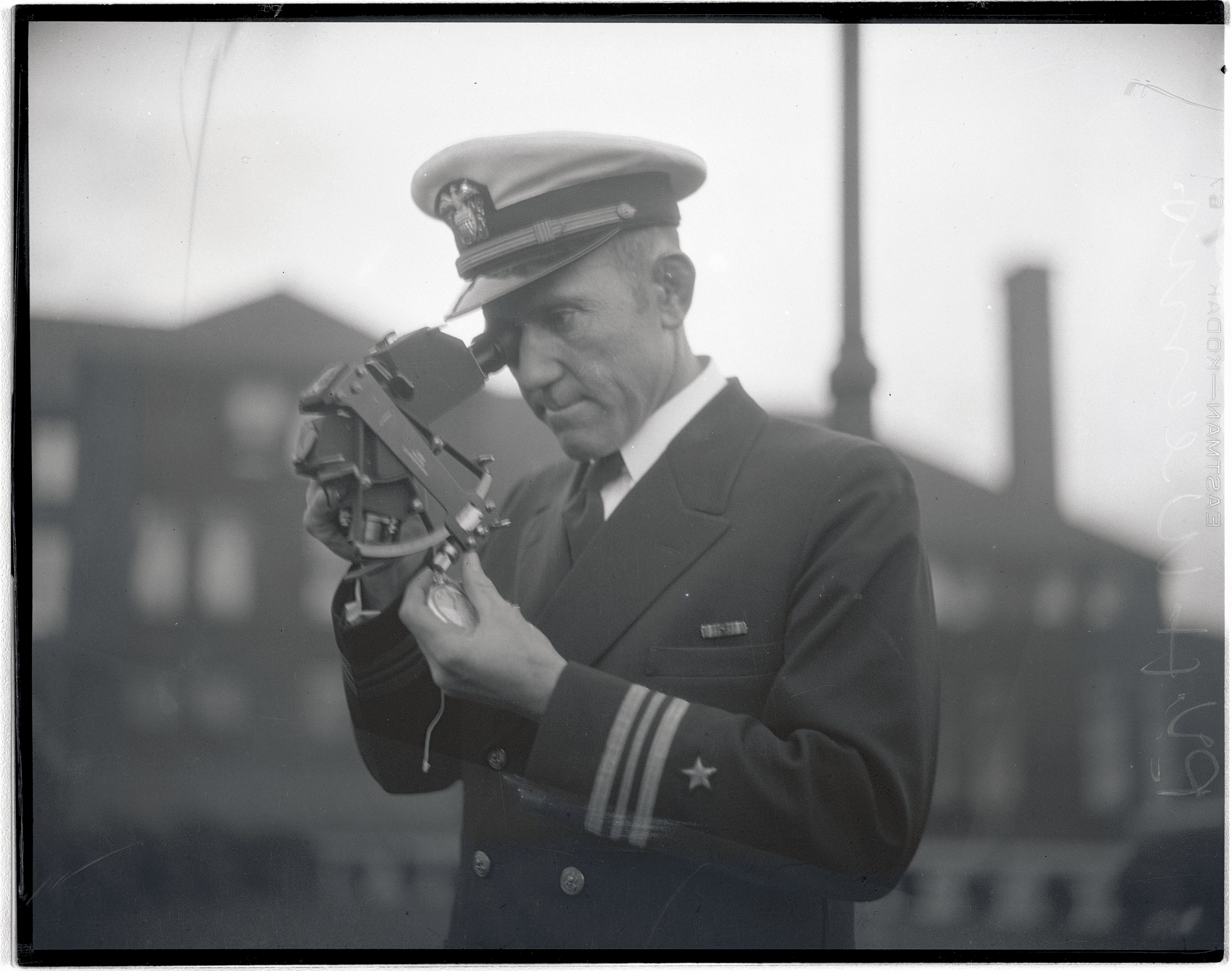

And yet, it’s puzzling as to why a feature as influential as the rotating bezel never really got its due. Conceivably, it’s permeated the design language for so long that most of us don’t think twice about who could be credited. Regardless, it’s high time we reaffirm the party responsible—a Naval Officer by the name of Lieutenant Commander Phillip Weems and his charge of the Longines Watch Company.

A Google search of P.V.H. Weems highlights several areas of noteworthy achievement… selection to the 1920 Olympics wrestling team, Convoy Commander for fleets in WWII, Naval Academy Instructor, and earning the distinction of “Greatest Living Navigator of his Time” (having re-written principles on aerial and celestial navigation and inventing the tools to stay alive while putting them into practice). The guy was a god-damn national treasure.

In sifting through all his accolades, you’ll surely find Weems’ association to Charles Lindberg, a name that should (hopefully) sound more familiar. Lindbergh was best remembered for his 1927 transatlantic flight in a plane named the Spirit of Saint Louis from New York to Paris. Not only was he the first to do this solo, he’d traveled further than any other attempt by 2,000 miles and made history by being the first to start and finish between two major city hubs. It was the stuff of legends that made the Air Mail pilot an overnight hero and global celebrity. Just to provide a little more perspective, Lindberg conquered a feat that claimed the lives of fifteen others after him—he was only twenty-five years old.

The significance of Lindbergh’s accomplishment led may other pilots to believe transoceanic flight was simply a matter of determination. While balls of solid rock could get you a long way, Lindberg knew it helped to have tech and know-how on your side—of which he had neither, but compensated with luck. In fact, on the day of flight, Lindberg jettisoned his radio and relied solely on dead reckoning, calculating his position from point to point while measuring airspeed. In other words, all he had was a clock and compass. It was a suicide mission written off by blind youth.

Though Lindberg had dismissed celestial navigation from his consecutive flights, goals of flying around the world meant he’d need to adopt better equipment and procedures if he were to stay alive. His research guided him to LTCDR Weems, who was enthusiastically conducting navigation experiments aboard coastal aircraft carriers. It afforded Weems every opportunity to introduce his prototypes for sextants, formulas, and the first “hack” watch developed with avigation in mind (the Second-Setting watch). The relationship fostered between the two of them changed the course of history for calculating variables in flight. Weems’ incomparable knowledge in aeronautics could now be dispersed through Lindberg’s celebrity circles, sometimes at Lindberg’s expense (having now exposed his “wing-it” approach to the masses).

The two collaborated on an instrument design that would build on Weems’ Second-Setting Watch, with the addition of a bezel that could measure direction based off the angle of the sun. Later known as the Hour Angle Watch, it only made sense for Longines to produce the commercial release; they were the official time-keepers for Weems’ landing across the Atlantic. Just as Jacques Cousteau was critical to the success of Doxa, Lindberg played a key role in cementing Longines’ ties to aviation. Released in 1931, the “Lindberg Watch” could be purchased all over the world.

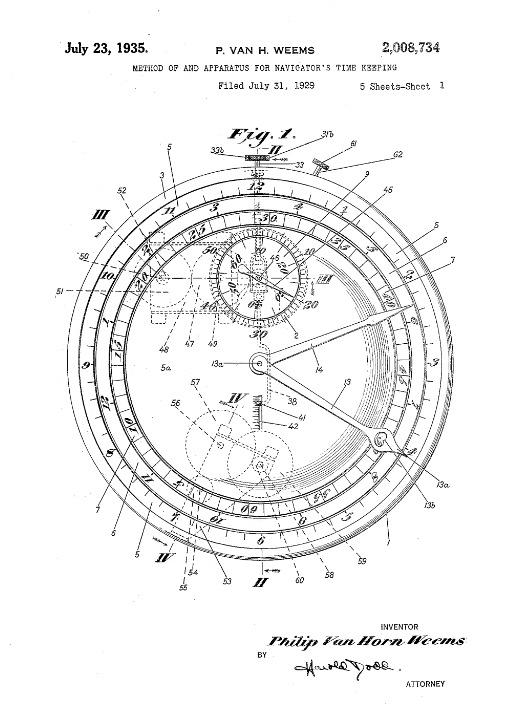

US Patent 2008734: The Rotating Bezel is Born

For a military pilot, the ability to track activity by the second wasn’t convenient; it was a total requirement. If he were to, say, drop a load of explosive ordinance over a target while traveling 200-300 miles per hour, several seconds late could mean missing the target entirely or (even worse) resulting in friendly fire. So, how would a watch capably sync up with the exact timing on command over a radio? The obvious answer would be to “hack” or halt the second hand by pulling out the crown to its fullest extent. However, 1929 had not yet seen mass-produced movements where hacking was an option—certainly not readily available for military requirements. The Hollywood line, “Hack on my mark: three, two, one” had not yet been conceived.

Weems’ solution was a simple one: utilize an external rotating bezel calibrated to seconds from 0-60. At will, this would allow the pilot to align its vertical zero position with the second hand or equivalent of any other time source (ie. a directive over the radio). The other inherent benefit was to eliminate the need for additional chronograph complications that would have put strain on the movement (start, stop, start, stop, etc). Born out of concepts like this was the Navy vernacular KISS (keep it simple, stupid), where if anything invited room for error, it was immediately eliminated in order to play to the lowest common denominator for intelligence or reliability. To this day, it’s why US uniforms still use buttons on their trousers instead of a zipper (so it could be easily repaired in the field).

WWII saw mass circulation of Weems’ A-11 design—too much, in fact, for Longines to keep pace with the demand. The company collaborated with Keystone Case Co. in Illinois and the patent was dispersed among Zenith, Omega, LeCoultre, and Movado. While there were various aesthetic differences in appearance, nearly all featured an additional crown that acted as a bezel lock that would clamp down with the slightest twist. This detail would later be appropriated by Glycine’s Airman. The concept of the rotating bezel on the other hand… that would be re-tooled and utilized by every other watch company for years to come.

Part 2 | Reviewing The Longines Weems Navigation Watch (Re-Edition) Ref L2.608.4 (limited of 3,000)

While we’re all accustomed to heritage re-releases today, Longines has been ahead of the trend for well over two decades. I can only speculate as to how sales reps pitched these novelties to Tourneau in the mid-nineties (my familiarity for horology had barely evolved past Burger King specials featuring Jack Skellington), but I imagine the response they got sounded something like, “Are you shitting me? It’s not even two tone.” Nonetheless, 1995 saw the re-editon of a Weems that was more or less a clone of an original (the Lindberg wasn’t so lucky), save for a few notable updates.

The Case

The dimensions for the case are modest 36mm wide and 10mm thin, a dress watch by today’s standards. While this might feel too small for some, the update should earn instant appreciation considering the originals were sized between 34mm and 27mm—both of which were intended for practical application. For the purist, Longines released a separate replica truer to the originals at 33mm. Lug to lug, ours is 42mm in length with room to accommodate a 20mm strap (thankfully). The case, itself, is polished stainless steel with a brushed bezel. True to the original, the bi-directional bezel is divided by sixty lines that would represent each second with black Arabic numerals for every ten second increment.

Part of what makes this watch such a unique reinterpretation was the choice for an acrylic crystal at the front (an obvious homage to its predecessor), with an exhibition caseback on the flipside protected by sapphire glass. It’s a delicate reminder that we’re still dealing with a “top notch” brand, although I can see how it would divide folks. Ultimately, it determines the watch as a novelty without playing down its practicality. What little room is left for around the window is packed with engravings to recap its significance, “Longines Weems Navigation Watch,” limited edition, etc.

The Dial

To the horror of some, there’s the inclusion of a date window. Although this is a common trade-off with a reissue, sensibilities will still be offended (regardless of the tasteful integration). Now that this has been noted, let’s move forward. You’re looking at a two tone dial that’s faithful to the original, bold numerals and patent marks included. The only deviation is the addition of “automatic” at the inner dial, a difference worth distinguishing when you consider the first was manual-wind. While there were a variety of Weems dials originally produced in the early forties, there’s no mistaking that this one was intended for the troops whereas the others were likely more approachable for civilian release. Key differences were the radium paint applied to the Arabic numerals and blued hands, as opposed to dauphine. Sure enough, with the re-edition’s release date in mind, this could very well be one of the earliest examples of “faux-tina” lume seen in the modern era watchmaking.

The Movement

The L619.2 is Longines version of the ETA 2892 movement, albeit with minor creative liberties taken for decoration. As the upper echelon of accessible brands, Longines has a historical preference for the classier of the ebauche movements, usually the 2892 over the 2824. While the ETA 2824 is considered a “workhorse movement,” the 2892 has a slimmer profile at 3.6mm (as opposed to 4.6), with a longer power reserve. Doxa, Stowa, and Hamilton are all fans of the 2824 and for the right reasons; they’re no-nonsense and reliable. However for the next step up, brands such as Longines and Bell & Ross will go the extra mile to showcase their 2892 with the perlage and Genève stripe finish behind an exhibition caseback.

In the case of the Weems, the slimmer profile allows the appearance to take on that of the original (the thinner, manual-wind caliber 10L). Ironically, the L619.2 is a hacking movement, which sort of defeats the original purpose of the bezel but that doesn’t mean there couldn’t be other practical applications.

The Strap

It’s always interesting to see how a brand chooses to finish strong for review and a lot of it comes down to the strap. The lizard hide band provided appears to be of decent quality (presumably real), having appeared to hold up fine from the previous owner’s wear. It’s padded, lined with calf skin on the underside, and held together with white stitching that contrasts with the black exterior. Under the steel tang clasp, additional leather’s present to make if feel seamless for the wearer. Lastly, the two keepers meant to retain the excess are finished with a barely noticeable blue thread along the sides. It’s a detail that would be overlooked by most, but a testament to Longines’ attempts to separate themselves from mid-range competitors.

I’m no fan of wearing some other guy’s skin cheese, so I opted for my own olive drab NATO strap—an AlphaPremier from Blushark for those curious. Considering the original intent of the watch with quality still in mind, I think it works better.

Final Thoughts…

Due to its simplicity, both in concept and design, the Weems watch reviewed may not be the best fit for the Longines of today where “Elegance is an Attitude.” Instead, they prefer the more ornamental of the options, LTCMDR Weems’ original Second-Setting watch. With its Breguet hands, pumpkin crown, Roman Numerals and internal rotating bezel, it’s far more in keeping with their design tastes. Unlike the Lindberg or the Second-Setting Watch which were exclusive to Longines, the Weems patented bezel design was distributed to four other watch companies, forfeiting perceived ownership. Last of note, tribute pieces such as the Avigation Bigeye, Heritage 1945, and Heritage Military already occupy the no-nonsense aesthetics territory in the current lineup. The closest we’ve seen to a recent Weems release with a rotating Bezel was the L2.741.4.

Should getting your hands on this limited release be in issue, no worries. If it’s anything that watch designs of late have taught us, it’s that “the old is new again.” Feel free to hold your breath… hell, you can use your bezel to time it.

Damon is based out of the Bay Area, where he’s a black sheep among Apple Watch loyalists. Having served as a Combat Engineer with the USMC, he believes a true field watch’s success is measured by how closely it compares to a “G-Shock.” Nonsensically, a background in design has guided his preference toward higher craft, as he struggles to become the lifestyle his watch tastes more closely reflect.

Great article and interesting watch. Thanks for the history.

You can still synchronize your non-hacking dive watch this way (like a Seiko 5). You know, if you are on a mission to blow a dam with Gregory Peck and Burt Lancaster.

GREAT article! I have been trying to fine of these and hopefully have just pulled the trigger! Can you let me know what the lug width is as I also want to get a proper NATO for it? Also – I’ve seen this same model with black dials – is that also historically correct in your knowledge? Thanks!!!