He probably wouldn’t be thrilled to know that I’m sharing it with strangers, but my father has a rather odd fetish.

It’s not stuffed animals, feet-related, or even anything to do with latex. Moreover, he should be lucky it doesn’t require spelunking through the dark net to get his fix because technology isn’t his strong suit. Even to this day, I’ve never confronted him on it but now that he’s retired, nothing’s left to side-step around what the heart desires. The old man really, really loves airplane noise.

To the casual outsider, they’d probably think, “Oh well that’s cute. He even has the bumper sticker that says it and everything.” But what they won’t know is that he’s had a hanger for the better part of thirty years with nearly a dozen different kit planes collecting dust (none of which he’s flown)… all as a cover for being in proximity to Cessna Skyhawks, Piper Cubs, Beechcraft turboprops, or any number of experimental home-builts powered by a car engine. The man’s got a CD loaded with P-51 flyby recordings. Moreover, he’s got another several featuring the heavy breathing from a dozen other aircraft like it—and he can tell you the difference between each and every one.

Now, once upon a time, I would have said this was weird… but it’s pretty much the exact treatment I (and likely many of you) dish out the second you see a chronograph from the sixties. “Oh cool—is that a Valjoux 72,” or, “is that a 7733” may be knee-jerk inquiries because you’re familiar with their layout and the knowledge that in-house movements were an uncommon commodity for most Swiss watch brands. There were only a handful of houses that produced their own calibers, the majority of which used generic but reliable engines supplied by third parties (referred to as ebauche). The heavy hitters were Venus, Lemania, and Valjoux (later ETA).

If you tend to follow vintage watches, you’d probably be able to identify the following ebauche movements based on their sub-dial arrangement with a single glance.

Calling them out may require a bit of brand background knowledge… maybe their association with costlier movements and whether or not they’re column wheel-based. Of course there are always exceptions to the rule, but the above were probably among the more prolific of the era.

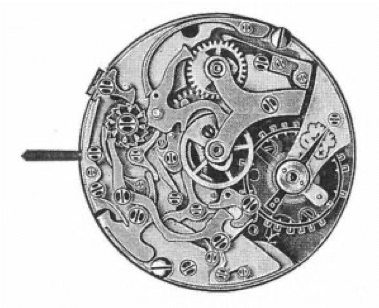

There is another chronograph arrangement that seems to never get any love but is worth a look. It’s in the very uncommon 12/6 sub-dial (or “up/down”) configuration and while it may be a little older, its production numbers made it a reliable favorite for distribution; it was known as the Venus Caliber 170.

Venus 170 Movement Specs:

- Type: Manual-winding, integrated column-wheel (8 column gear)

- Jewel count: 17

- Power reserve: 40 hours

- Complications: 2-button; start/stop chronograph

- Size: 6mm height, 28mm width

- Frequency: 18,000 a/h

- Hands: (vertical register layout)

- 30-min chrono hand at 12:00

- 45-min chrono hand at 12:00

- central 60-sec chrono hand

- central hour hand

- central minute hand

- small seconds hand at 6:00.

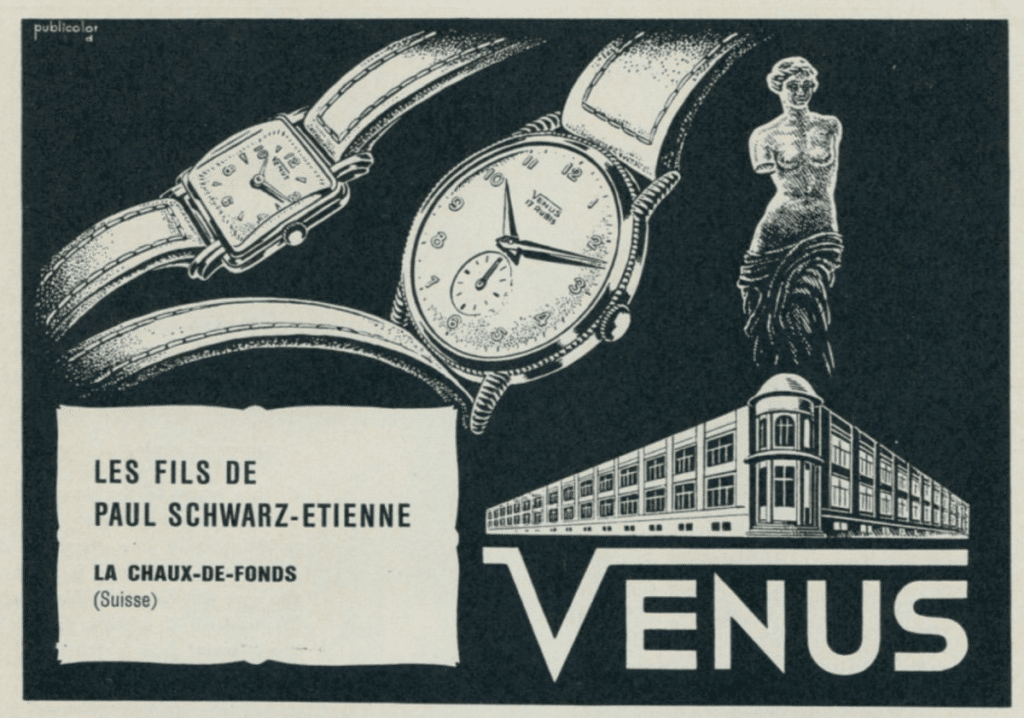

A (Brief) History of Venus Movements

Established nearly a century ago, Venus started producing calibers in 1923 and gained a foothold for demand with the release of their first chronograph ten years later, the Cal. 103.

To say that they were “pioneers of ebauche manufacturing” would be an understatement. The reliability of their column-wheel movements made them a go-to source for key players with market dominance, further enhancing their reputation. Eventually this granted Venus the confidence to start signing the dials of their own wares.

While they produced their own “three handers,” these low cost alternatives weren’t producing enough liquidity to justify their development. They were forced to sell their assets to rival Valjoux in 1966, including the recently-released Venus 188 movement—the foundation for what would become the Valjoux 7750 we all know and love today.

Mass-Produced and with Mass Appeal

Manufactured between 1942 and 1960, the Venus 170 was mass-produced out of the need for supplying a single chronograph capable of being dressed-up or dressed down and across all markets.

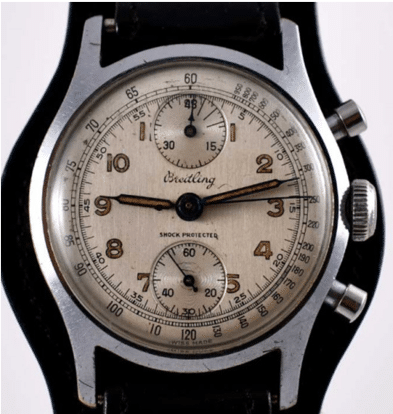

It was utilized by a multitude of Swiss brands, including Wyler, Gallet, Breitling, Wittnauer, and Heuer, however most were associated with the more obscure (and defunct) names such as Leonidas, Buren, Silvana, Telda, Eloga, Siduna, Elbon, Helbros, Olma, and Clinton. They were commonly outfitted with telemeter scales for gauging the distance of objects in relation to noise. In response to the spike for medical personal, they were also widely available with a pulsometer dial.

The combinations for appearance produced was indicative of the networks between companies and parts factories of the era. Some cases were chromed while others were stainless steel and even 18kt gold. The consistency was complicated further due to a steel shortage (war-related) so it was common to have stainless backs and cheaper, plated fronts. Just from a dial standpoint, the variety was staggering. Roman numerals, Breguet numerals, snail track dials, and Art Deco styling all found their way without any sort of discrimination for brand.

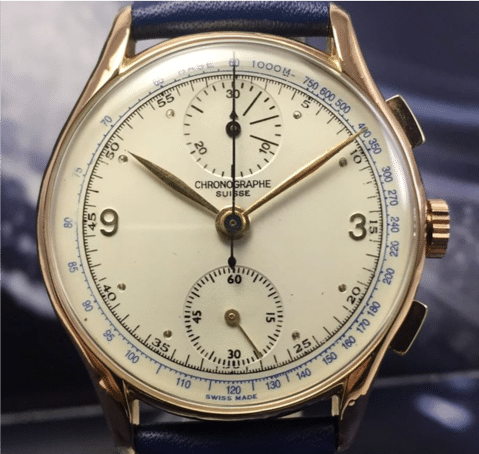

Stigma for “the Generic” and Chronographe Suisse

Considering the aesthetic variety to feature the 170, this could be a bit daunting for a collector where provenance is paramount and integrity becomes questionable. Similar to how there were several co-signed dials in the 70’s that evidenced the merging of Movado and Zenith, there were a ton of dials that would share the appearance of a Chronographe Suisse variant. The relationship, however, was quite different.

Chronographe Suisse was one of the more prolific parts suppliers for Swiss brands of the era. Sure enough, most folks probably hadn’t even known that it was a company name simply because it was the literal nature for what it was describing. Their network as a parts supplier was near-limitless. If you were to travel in Europe and simply wanted “a Swiss chronograph,” there was a good chance your accessible, off the shelf purchase was sourced by Chronographe Suisse and then switched out with signed components. In other words, the only real difference between a Breitling and the “generic” Chronographe Suisse alternative may have been the quality of leather strap included.

Most collectors are nothing if not purists. This is partially why manufacture companies (houses that produced everything under the same roof—including Movado at the time) tend to be more desirable from a collecting stand-point. They’re easier to catalog and cater to the sensibilities of a completist. The flipside of the coin for a Venus 170 is that one may have to make peace with a possibility of “frankened” parts.

Three reasons why the Venus 170 is still remarkable for today:

1. Pioneering “Quality on a Budget”

The 170 marked a transition in manufacturing approach that catered to greater efficiency with mass-production, a burgeoning direction in the wake of WWII.

In order to supply the 170 at a more economic costpoint, parts typically milled from a single sheet of metal were replaced with wire of the appropriate gauge and resistance. The result was a savings in cost across time, labor, and materials used, all the while making it easier for repair. Additionally, it capitalized on the evolution of machine-driven manufacturing.

2. The rare “Up/Down” Subdials.

While there were several ebauche dual register movements circulated in the past, far fewer were produced with this vertical layout. One of the few exceptions to this would be the Valjoux 77, produced between 1946-1950, accounting for less than a quarter produced by comparison. The most easily identifiable giveaway under the caseback would be the bridge and more obvious inclusion of wire springs.

There are only so many different versions floating around from the pre-quartz era (or even today), making the Venus 170 one of the more “quirky,” recognizable configurations in existence.

3. Low cost point

Nobody seems to care about the 170… which makes it relatively inexpensive. One could easily acquire vintage Breitlings, Gallets, or even Heuers because they’re so poorly documented and smaller in size.

Mint examples can be acquired in solid gold around the thousand dollar mark. Could a 170 ever be considered an investment? Probably not (unless a large horology-based retailer/lifestyle branding/watch insurance “dot com” would deem otherwise).

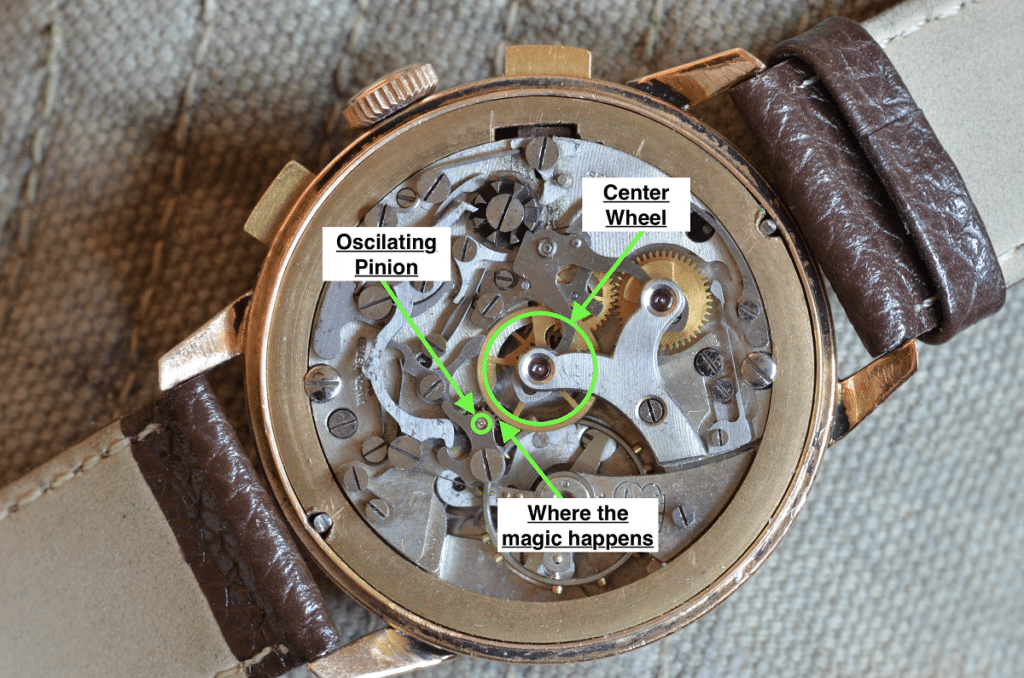

Deconstructing the Venus 170 Movement

Let’s split some hairs for a moment to reaffirm what makes a movement “desirable.”

First: Noting whether or not the chronograph is column-wheel based—an indicator that the engine was conceived by and for those with the utmost reverence for traditional watchmaking. The alternative would be a “cam lever” movement which is simpler in design, allowing for greater tolerances and (potentially) cheaper production.

Second: Consideration of the engagement design (or coupling) for kickstarting the chronograph function. More technically, the options here are vertical or horizontal clutch (our 170).

With vertical, the gears are always engaged and preceded by several levers talking to each other for a smooth start when actuating the timer. On the other hand, horizontal clutches skip the flirty foreplay, engaging gears on command—similar to a drunken hook-up that harkens back to your college days where the end-state’s the same however less graceful and more direct. It’s in “skipping this courtship” that watches invite the greatest range of criticism for quality.

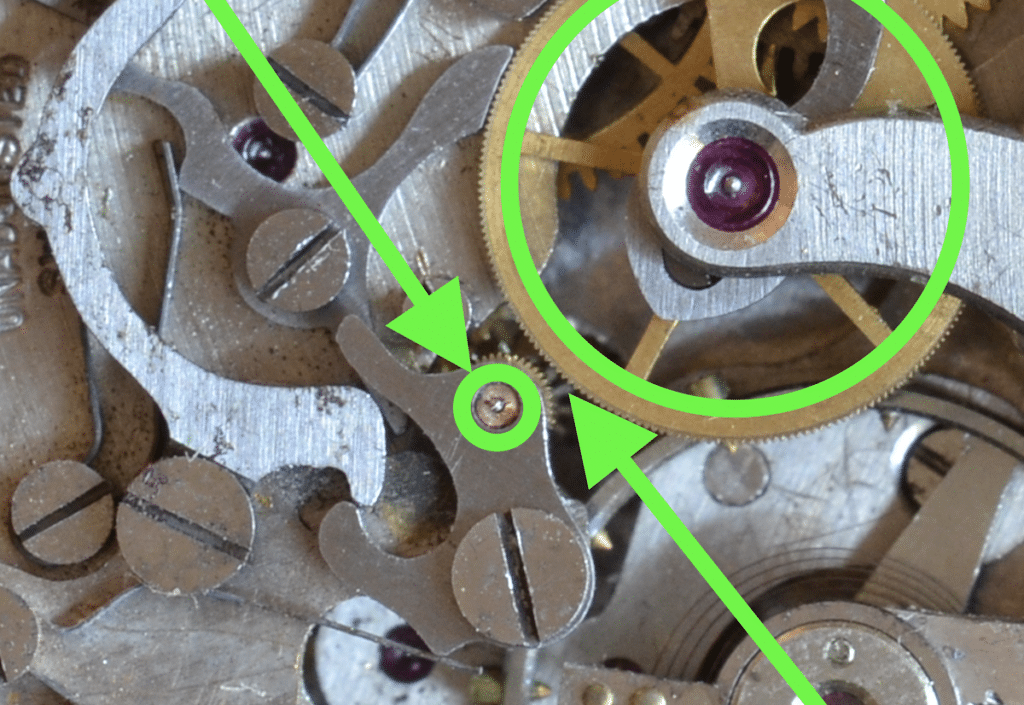

The most simple but effective means for brokering this point of contact is known as the oscillating pinion—something of an unsung hero in horology circles, and featured in the 170. Also known as the “rocking” or “swinging pinion,” it’s the conduit that transfers activity from the movement’s seconds wheel (constantly engaged) to the chronograph seconds wheel (conditionally engaged).

The chronograph center wheel is actuated by oscillating pinion’s gears smacking into place where as before there wasn’t contact. Once the teeth line up, a connection is established that powers the time keeping. This is halted by the cog being yanked away from the center seconds wheel. It’s extremely practical at the risk of being considered “less refined.”

The design was patented by none other than Ed Heuer, himself.

About the Hands-On Example Observed

This particular brand is a Leonidas, a name later associated with Heuer. At 35.5mm in size, it has minimal wrist presence but it’s actually larger than what it could have been, considering cases ranged down to 32mm (typical of sizes from the 40’s and 50’s-era chronographs).

Despite being solid rose gold, the case is very light and thin, no doubt an attempt to reduce its cost in materials for production. It’s dial is impeccably preserved (almost suspiciously so), featuring a pulsometer with baroque Breguet numerals.

On a beat rate counter it clocks in at -41 s/d. Not bad for a 65 year-old watch with no service history to speak of from the previous owner. By comparison, my ETA 2892-based chronometer-rated Breitling Montbrillant is slow by nearly three minutes a day and was produced thirty years later.

Final Thoughts:

It would be my assumption that Venus conceived the 170’s mechanics with two goals in mind: First, to maintain quality in spite of cutting costs. Second, to implement Heuer’s oscillating pinion design—a reliable, if not “lean” approach to manufacturing the movements, themselves.

In a time where watches have never been more expensive, with companies continuing to look backward for inspiration, “up/down”-based designs seem to continue standing by in the shadows.

Most significantly, the Venus 170’s appearance and historical importance can address a void behind a collector’s perpetual longing—diversification of an iconic line-up without leaving you dirt floor-poor.

Damon is based out of the Bay Area, where he’s a black sheep among Apple Watch loyalists. Having served as a Combat Engineer with the USMC, he believes a true field watch’s success is measured by how closely it compares to a “G-Shock.” Nonsensically, a background in design has guided his preference toward higher craft, as he struggles to become the lifestyle his watch tastes more closely reflect.

Dug the article, the specs and the arrows! We’ll written and engagingly presented for peeking at the movement.

Thanks, Brad! Talking movements can be dry stuff so I’m glad it was well-received.

Your article was witty and factual. I thoroughly enjoyed it. I have my grandfather’s Orfina chronograph, with the Venus 170 ticking away. I just had it serviced. It clocks in at +/- 30 seconds with the amplitude being 270+. The movement is factory decorated and is housed in a 18 carat yellow gold case. The watch and movement are in near new condition. It’s a keeper!

Hello Damon, Excellent article! I located this when searching for a site that has ‘images’ or diagrams of all the Venus Chrono ebauche’s they sold. why? because I’m trying to locate

who made the ‘chrono’ ebauche for a Zais Watch Chronograph. there are ‘no’ hallmarks (or Movement Mfg mark located on the plates.

I have a number of Chronograph books and catalogs (I’m a watchmaker) that I’ve poured through

to identify ‘who’ made this 2 register chrono. so far, nothing.

do you have any reference links for chronographs? this one dates to the 30’s/40’s.

thanks

Bill

Zais Watch was one of the Breitling trademarks.

thanks for this blog post im getting a rolly branded venus 170 soon