There’s no greater blessing than bearing witness to an iconic watch brand’s reputation crash and burn, it’s legacy in total ruin, and hopefully forgotten by the masses… It means getting your hands on their earlier stuff is that much easier.

Such is the case with Movado.

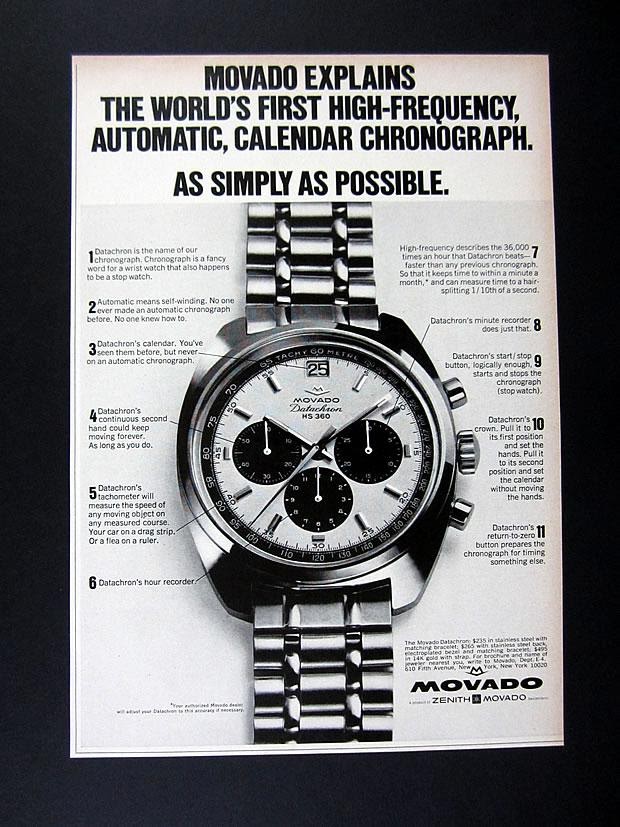

Today, Movado is best known for their minimalist “museum dial” and its variety of fashionable iterations available in every mall across America. More often than not, they’re outfitted with sapphire crystals and Swiss-made quartz movements. They are a staple to many enthusiasts’ first discoveries of brand awareness and accessible luxury. And, prejudices aside, it’s fair to say they’re good at what they do. Beyond aesthetics however, “what they do” isn’t much, and it’s probably why you’d be challenged to find any watch journalism covering their accolades today.

Quality that’s lost its way is nothing new for the watch world; there are a ton of other brands that exist as shadows of their former glory… Bulova, Wittnauer, and in some respects, Longines are among them. But none get shat upon by horological elites quite like Movado. This may say more about how far the they’ve descended than their current offerings of today. Regardless, this is not a bad thing, and perpetuating the blanket statement that Movados are “less than” means there’s tremendous value proposition to discover from their earlier pre-quartz line-up.

As such, please consider the 1969 Movado Datron Sub-Sea as Part 1 of this 2-part Movado appreciation series. Be sure to check out Part 2 for a Pre-Museum Dial History of this iconic brand.

Reacquainting Ourselves with the Movado Datron Sub-Sea Chronograph

• Year released: 1969

• Movement: Caliber 3019 PHC, automatic chronograph (manual-wind optional), El Primero with date function, 17/31 jewels (depending on region of distribution), 36,000 bph, 51 hr power reserve.

• Bracelet: steel, link with folding clasp.

• Dial: triple register black and white panda, with date at the twelve.

Zenith-Movado-Mondia Holdings Group

Before expanding on the Datron’s characteristics, shedding light on the relationship between Movado and Zenith would allow for greater perspective. A common misconception is that Movado is a less-expensive version of Zenith (akin to Bulova/Caravelle). In actuality, the two started as separate entities but understood the value in joining forces for building on their R&D department to combat the rise of the electronic watch.

Because of this relationship, the two watch brands were tied to the hip in cohesion for both their line-ups. Secondly, Zenith took interest in acquiring Movado because they were restricted from marketing their watches to the United States due to trademark territory disputes with Zenith Electronics. The two were unrelated companies that only shared a name by coincidence. Ironically, Zenith Electronics would later purchase the majority of shares for Zenith watch company in a move that would become symbolic of the quartz dominance of the seventies.

To side-step this marketing restriction, Movado “became” the Zenith brand of the American market (although Movado was still widely available in Europe). Many watches produced in the late sixties and early seventies were completely identical in parts and materials used. You could pop off a Movado case-back and see a Zenith-signed movement.

This would even include sharing dial appearances with exception to interchanging the name from Zenith to Movado. In some cases, both names were signed alongside each other. Depending on the watch, Movado produced a greater number of cases in solid 18k and 14k gold options.

Oops, almost forgot about Mondia. Real quick, so… Mondia actually was kind of the redheaded stepchild of the trio. It’s not that they were poor quality, per say. They just had the smallest budget to work with across the board. Being the most affordable, they were provided very little in the way of marketing support. In the end, the struggle to stay relevant against the quartz options was very real.

The Datron Engine: A Story of its Own

Powering the Datron is the base Caliber 319 PHC movement. However, you’re probably more familiar with its alias, “El Primero,” as marketed by Zenith. The two are virtually identical. As “the first automatic chronograph,” attempts to discuss its merits in a thousand words or less is a challenge. Still produced to this day, it’s best remembered for its 36,000 beats per hour that are capable of measuring speed up to a 1/10th of a second.

As partners, Zenith sought to leverage Movado’s experience designing complications from the forties, and their more recent development of the Kingmatic HS 360 (36,000 bph) as building blocks that would become integral for the Primero’s production. Several generations later, the Primero’s design served as the foundation for the Rolex Daytona.

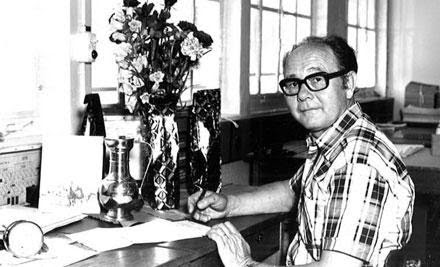

Above: Charles Vermot, the horological hero/punk rock pirate responsible for telling Zenith to go stick it after being order to destroy the Primero prints. His rebellion saved the company after the Quartz phase subsided. Everybody say, “Thank You, Chuck.”

This Datron utilizes a variant movement (3019 PHC) where the date window is located at the “12” instead of the typical location between the “4” and “5” markers. It’s exclusive to Movado; you’ll never see this consideration for balance incorporated into Zenith’s line-up from the era. The movement’s overall height is 6.5 mm, exceptionally flat considering its complications (for its day). As with the other triple register chronographs, the continuous running seconds is on the left subdial. The minutes are documented at the right (thirty-minute cycles), with up to twelve hours recorded at the bottom.

The second hand sweeps with an uncommon fluidity you’d expect from a high-beat movement. Some owners might tell you, “When pressure’s applied to the top pusher, there’s a noticeable difference in less force required to start the timer. This is an integrated column-wheel chronograph—where unlike the modular Calibre 11 Heuers—the mechanics here are more fluid and deliberate.” But as an owner among them, I can’t really tell any different… I’m just glad it keeps time to within 20 seconds a day after fifty years of use.

The Case

The Datron is housed in a stainless steel tonneau-shaped case with a profile that “swallows” its lugs. It’s overall form is a sporty reminder that design was shifting toward edgier seventies-styling. It may not be a timeless look, but it was more conservative than the Primero A384—with angles so aggressive that folks at Zenith pretty much said, “Screw it. Next time, let’s just call it ‘the Defy.’”

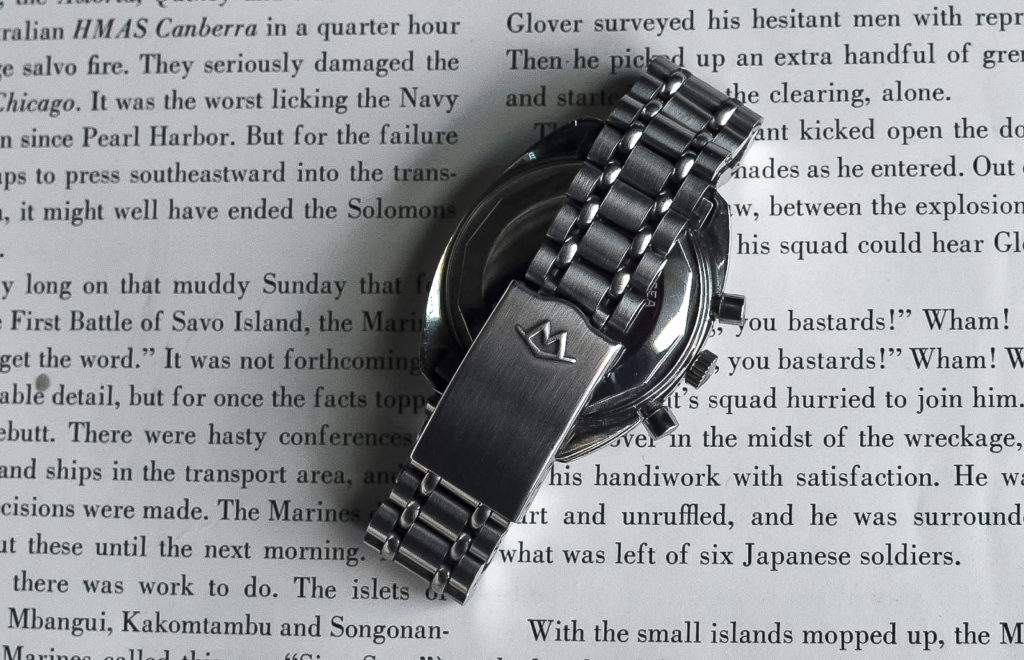

The Movado’s case front surface is a brushed texture in the direction the body’s curvature, and polished on the sides. While the crown is signed with Movado’s fifties-era “M,” the case-back is plain and without any unique appearance with exception to the engraving, “Sub-Sea.” Contrary to what the text would suggest, this was by no means a diving watch. “Sub-sea” was merely a designator to communicate water resistance in the same way that Omega had advertised a Seamaster. However, other models including the Super Sub-Sea made good on those who were left wanting something more.

With dimensions of 38mm across and 43mm lug to lug, it’s decently proportioned with modernity in mind, aided more so by the lack of a bezel. Other case alternatives included gold plaque, 14k solid gold, and 18k solid gold.

The Dial: A Balancing Act in Aesthetics

Fans of the original Hamilton Chrono-matic would find themselves right at home with the panda dial and reverence for symmetry shared by the Datron. It’s right around here that I need to be transparent about my prejudice. I’ve never been a fan of the date windows, even less so of ones located between the “4” and “5” markers for the obvious reason that the balance is compromised. Not wanting to interfere with lower the sub-dial, Movado made the decision to set the date in place of the “12” marker at the top. In doing so, the date window actually brings more balance to the piece, complementing the sub-dials with the black date placement.

Circling the dial’s outer edge is a black chapter ring with a tachymeter scale, made visible by contrasting white print. Just inside the predominantly white face we see the fine black lines marking 1/5th of a second. With exception to the date position, every five minute interval is identified by silver applied indices with luminescent accents, three of which are intercepted by the black sub-dials. I can empathize with folks who get riled up by Arabic numerals getting cut off, but the “3, 6, and 9” markers are perpendicularly positioned to accommodate for the dials, also a purposeful consideration for three hour increments. Mimicking the appearance and width of the indices, are the polished baton hands.

Just below the date window there’s the silver applied logo “M,” followed by three lines of centered text, “MOVADO,” “Datron,” and “HS 360.” Each line tapers more tightly toward the center, mindful of the remaining space. Whomever had been put in charge of this was an utter Nazi for symmetry. Oddly enough, omitted from inclusion is any mention of “Automatic.”

Other dial options included a gold gilded dial (for the gold cases) and two “inverse panda” versions offering either blue or black with white sub-dials.

The Bracelet

The bracelet that comes stock with the Datron is stainless steel with a three-fold clasp. Physically, it appears to be a combination of brushed finish links held together by beads of rice “grains.” The clasp is a brushed finish and signed with the Movado “M.” At the time of its release, Movado was known to have partnered with Gay Freres for outsourcing their bracelet manufacturing (same for Zenith), however there are no other identifying characteristics suggesting this was the case for this particular model. This would suggest Movado had made it in-house, and that it’s unique to this particular model. It’s lightweight, comfortable on the wrist, and capable of micro adjustments within an inch based on the clasp’s setting.

Final (Subjective) Thoughts

The Datron is not a “Poor man’s Zenith Primero.” Zenith leveraged Movado as their partner to market their goods in the States, where they couldn’t be offered for legal reasons and maximized the opportunity for quality whenever available. Although it’s easy to take pot shots at Movado for reprioritizing its interests throughout the years (and changing of hands since then), this should not detract from their earlier successes. The original Datron is very much its own thing. The Movado of today did eventually attempt to look backward and re-release the original, however it’s engine was replaced with an ETA 2894-2 (37-jewels).

The 319 PHC/Primero movement represents the pinnacle of engineering for its time. It was a desperate attempt to outshine a tuning fork and battery through massive pooling of resources, that in the long run, contributed to laying the groundwork for many other companies in suit. Even after all the hoopla surrounding the competition of the Caliber 11, Tag Heuer conceded to integrating the Primero movement into their “in-house.” Even more blasphemously, it outfitted their Monaco.

What’ll finding one of these cost? Like any other watch, condition’s everything and the traditional panda dials tend to be more desirable. Following eBay, I’ve seen them anywhere between $1100 for gold plaque – $3700 for NOS solid 18k gold. Nothing to sneeze at, but considering its legendary in-house movement, you’d be pressed to find a better value in any other vintage piece on the market.

Continue to Part 2 for a Pre-Museum Dial History of Movado.

Damon is based out of the Bay Area, where he’s a black sheep among Apple Watch loyalists. Having served as a Combat Engineer with the USMC, he believes a true field watch’s success is measured by how closely it compares to a “G-Shock.” Nonsensically, a background in design has guided his preference toward higher craft, as he struggles to become the lifestyle his watch tastes more closely reflect.

Interesting article, between 1969 and 1981 the cooperation between Zenith & Movado lead to the Datachron & Datron HS360 chronographs… which have been used by many NASA engineers and by Skylab-4 commander Gerald Jerry Carr during 84 days onboard Skylab space station between November 1973 and February 1974.

Get out! I had no idea. That is some quality research!

Hi Damon, with the cooperation of MoonwatchUniverse “Snuck into Space”

https://www.hodinkee.com/magazine/snuck-into-space