How do you measure success when you’re up against a titan? Is success defeating it completely? Is it forcing a concession from it? Or is it just ensuring that those around you don’t kowtow to its every word?

Rolex is a titan of the watch industry. It consistently tops the charts in global watch sales, and wearing a Rolex is often seen as an identifier that the wearer is wealthy and/or successful. As many complaints as there are around the “overhyped” nature of their watches, no one can deny their quality. Quality, though, is only part of the story. No one will know how good your product is unless you can market it appropriately. That’s where Rolex’s reputation with enthusiasts becomes more murky.

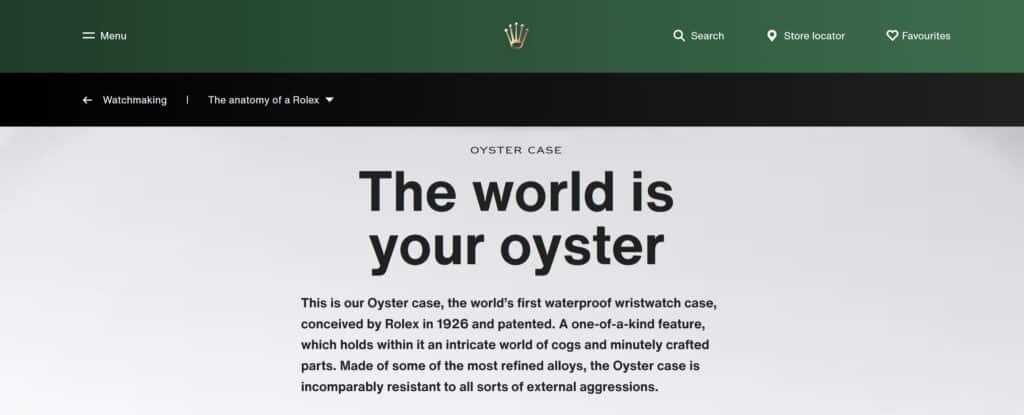

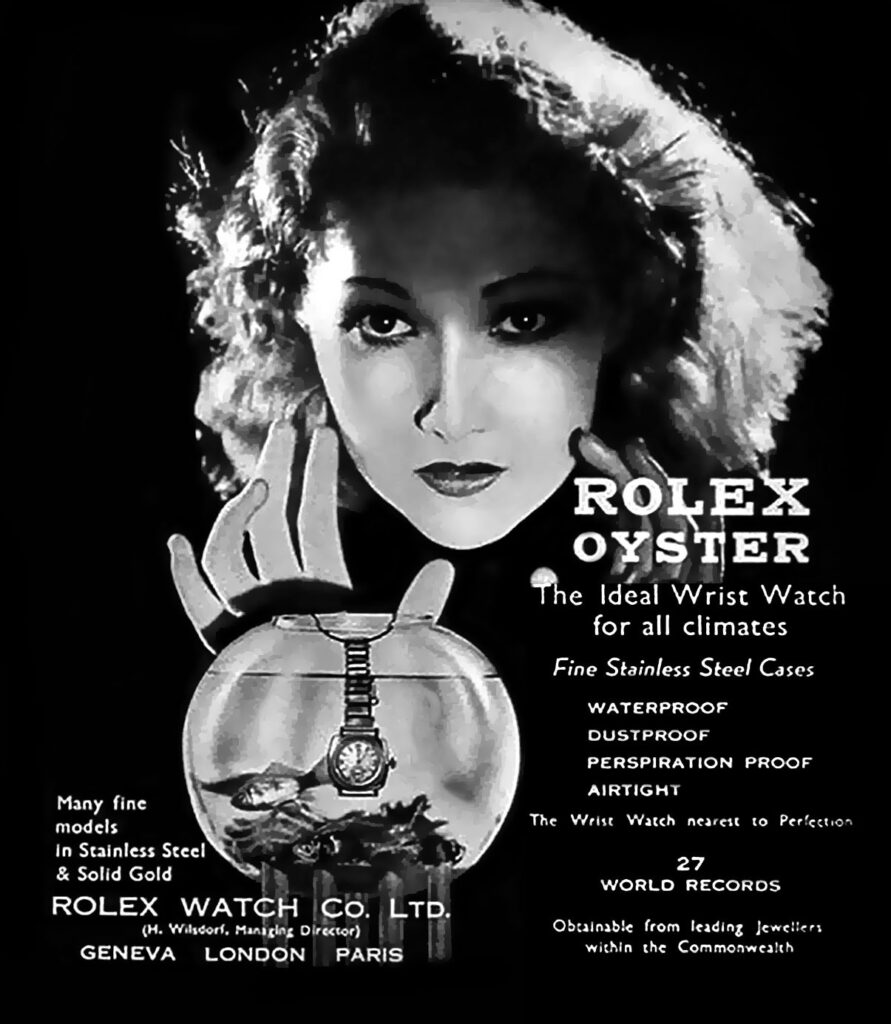

Watchmaking is full of gratuitous claims and overinflated marketing. One of the oldest is Rolex’s claim, still on their website today, that the Oyster Perpetual was the world’s first waterproof watch in 1926. These claims were the basis for Rolex’s reputation for reliability and ruggedness. While Rolex’s Oyster Perpetual was highly water resistant, it was not the first company to create a successful water-resistant design. That title belongs to Charles Depollier, who was fulfilling orders for the U.S. Army as early as 1919.

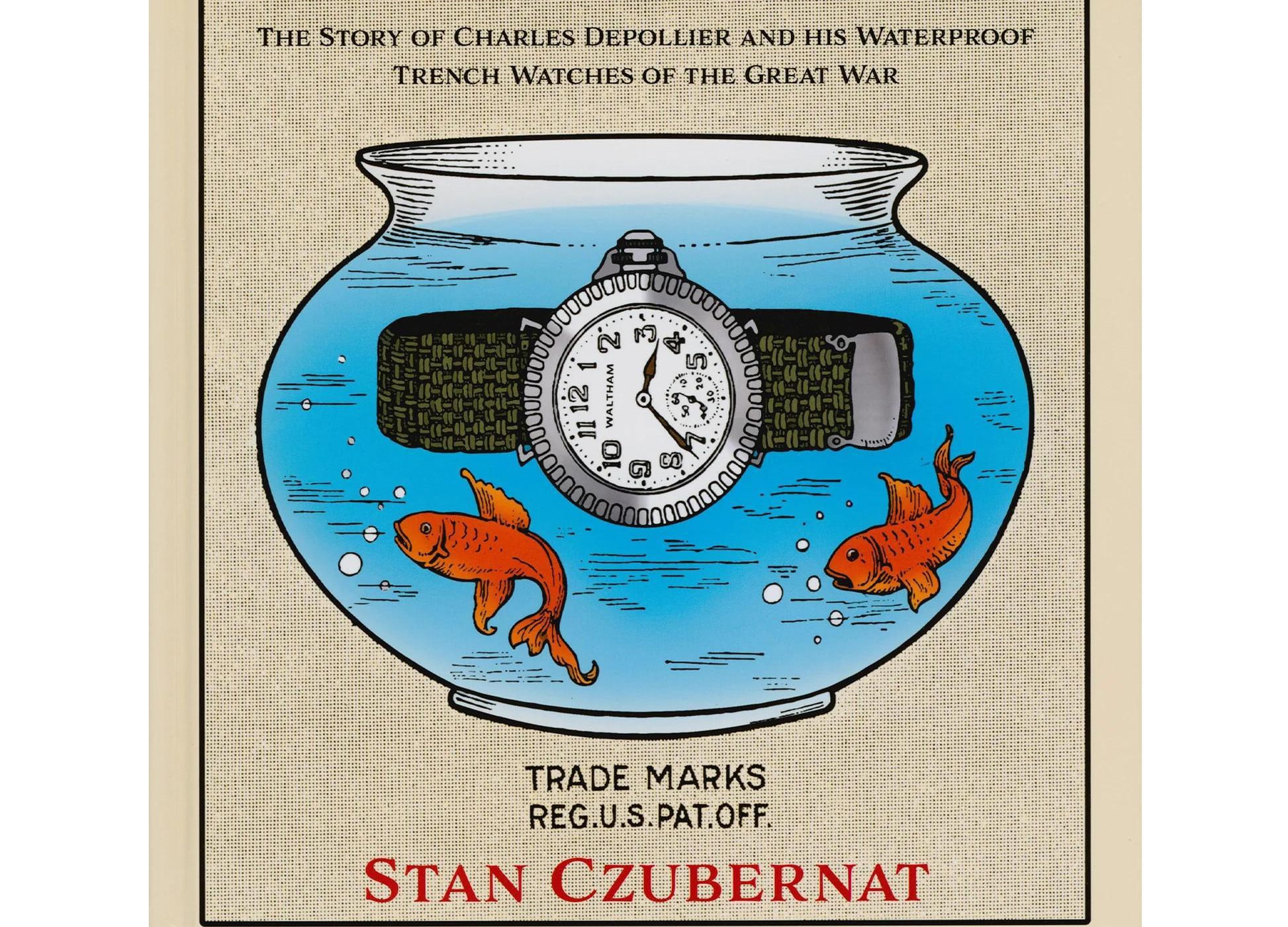

In his book The Inconvenient Truth About the World’s First Waterproof Watch, Stan Czubernat definitively demonstrates that the first waterproof watch was developed by Charles Depollier, an American watch casemaker. Mr. Czubernat presents irrefutable evidence that, contrary to Rolex’s claims otherwise, Charles Depollier invented the world’s first waterproof wristwatch case.

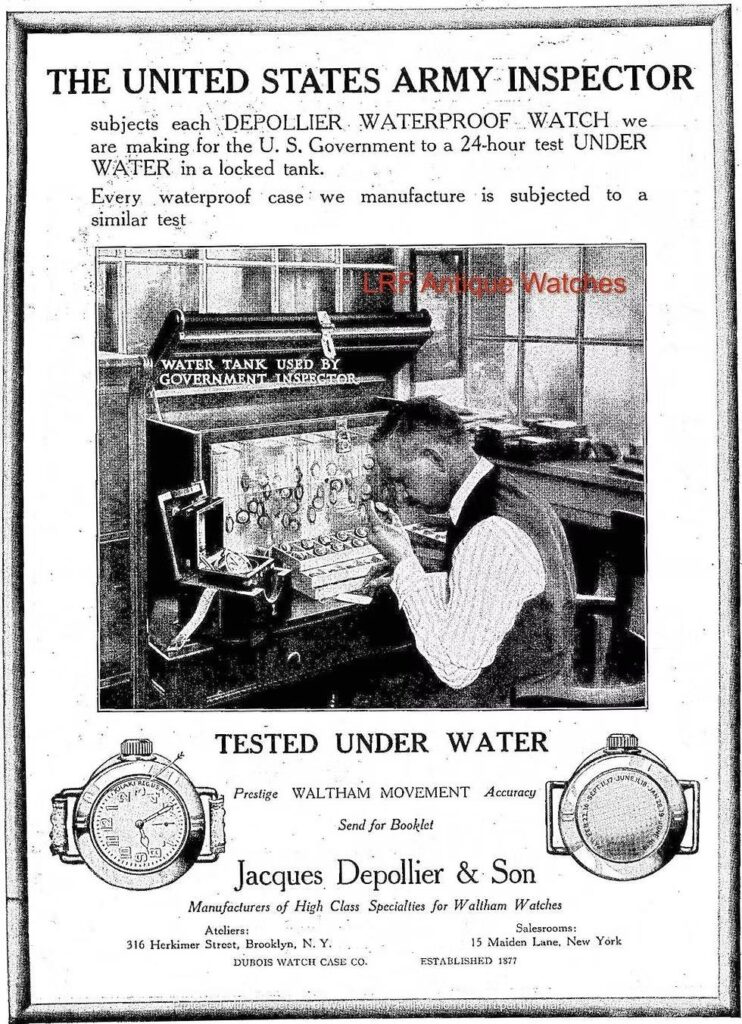

The Inconvenient Truth, though it officially caps out at about 200 pages, is in reality much shorter. The vast majority of the book is given over to screenshots of pdf files, the source material that Mr. Czubernat bases his claims on. There are military documents, court files from lawsuits, and pages from the various patent applications that Mr. Depollier’s company filed in the 1910s. Mr. Czubernat spent several years conducting research on the topic, going so far as to fly to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. to review U.S. Army watch procurement documents from the Signal Corps.

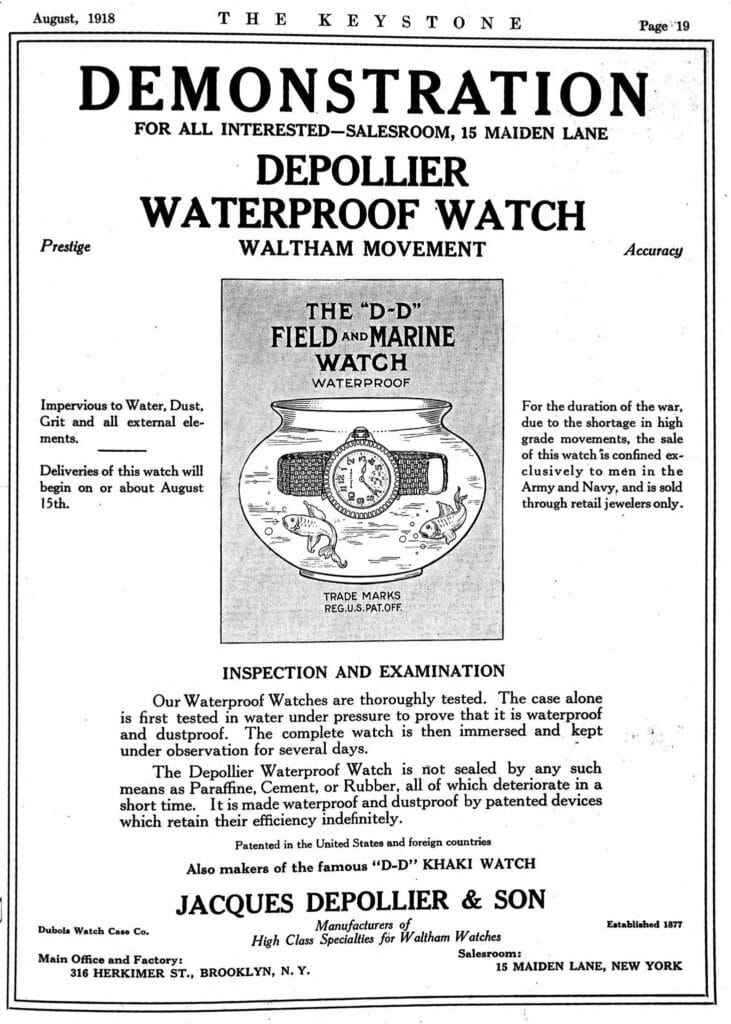

Interestingly, he notes that he used available commercial AI programs to help him collate sources. Reaching out to other collectors, he also obtained older Depollier advertisements promoting their watches. His most compelling point of potential copycat behavior by Rolex is in their marketing – in 1926, they released advertisements with their new Oyster Perpetual suspended in a fishbowl – the exact same marketing technique used eight years earlier by Depollier.

This is not Mr. Czubernat’s first foray into this topic. He has written two other books on trench watches – one for Waltham watches, and one for Elgin watches. In 2023, he received the National Associations of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC) award for his research in this specific horological topic, spread across his three books. This gives his claims and results more credibility, as a body of watch enthusiast panelists determined his argument and evidence both sound and worthy of recognition.

While the book format certainly presents the reader with the materials that back up the author’s claim, it remains wanting in terms of narration. The biggest flaw with Mr. Czubernat’s book is that he does very little to convince the reader why they should care about Charles Depollier. There is very little about his life, why his technology wasn’t used by more companies to improve their own watches, or why Rolex’s claims about the Oyster Perpetual’s marketing in 1926 are damaging to the watch community, other than that they are incorrect. Depollier is long out of business, and Rolex’s Oyster Perpetual case did have some effective water resistance.

Their product was still good, even if it wasn’t technically the first. There is no evidence that Depollier lost business to Rolex over their claim. Rolex’s method of improving their watch’s water resistance was also different from Depollier’s – the crowns on Depollier’s were locked down using a “bayonet” mechanism that isn’t present on the Oyster Perpetual case. If he can better articulate the “why” of the story, Mr. Czubernat has an excellent case against watch marketing as a whole.

Despite my concerns with his ability to project the message, I wholeheartedly agree with Mr. Czubernat in spirit – the truth is important for the truth’s sake, not just to serve a specific end. As in other areas of our lives, it is important that we as consumers parse through overblown marketing claims to gain a fuller understanding of the products and the hobby we enjoy. A claim that Rolex created a good, water resistant watch in 1926 is one thing. A claim that they created the “world’s first waterproof wristwatch,” is something else entirely, and lends an additional credibility to them that they did not earn.

To answer the question I posed at the top of the top of the article, I do not think that Mr. Czubernat effectively meets his own criteria for what he views as success – the eventual redaction of Rolex’s claims to have created the first waterproof wristwatch. I do, however, think he has set the foundation for doing so – if he can put together a narrative about why those most likely to buy Rolexes should care. I recommend this book to watch enthusiasts who want to understand more about early attempts at increasing water resistance in watches, and who appreciate a thoroughly-researched product. I will reiterate, though, that this is a reference product, not necessarily a narrative-driven one.

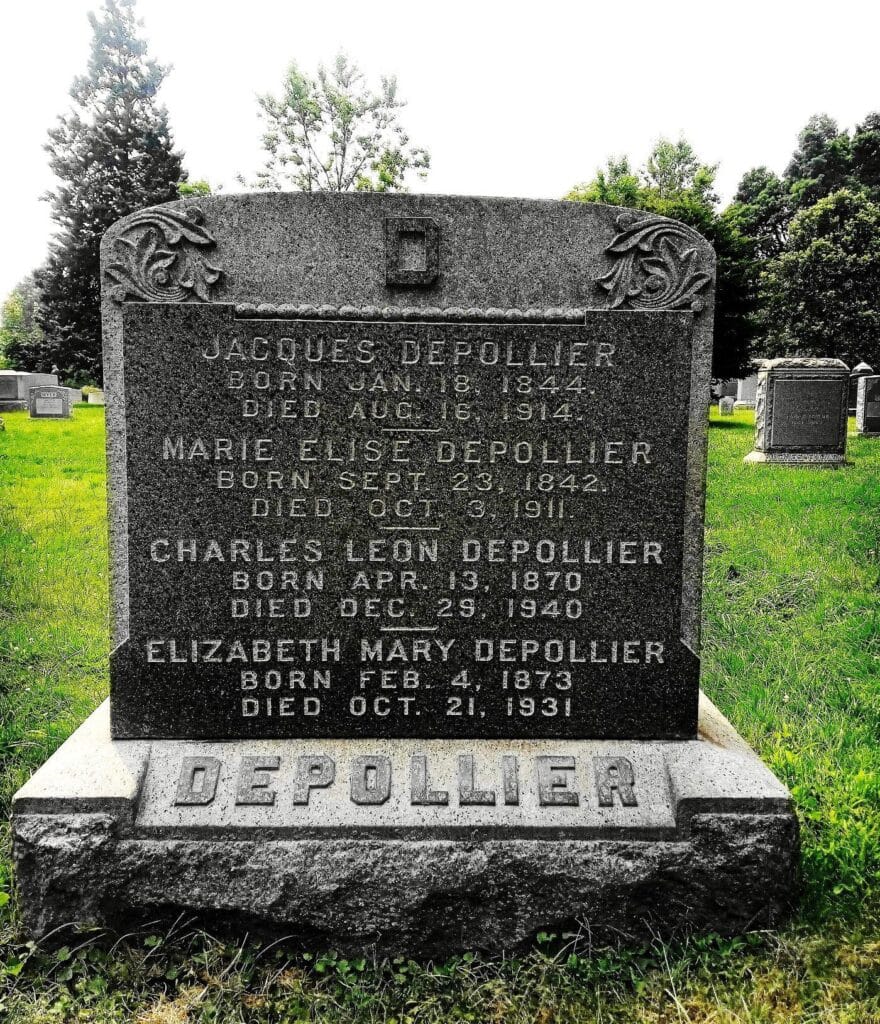

The book ends with a story about Mr. Czubernat and other volunteers finding and restoring Charles Depollier’s grave. It’s this kind of human narrative that the rest of the book lacks, and a line of storytelling that I hope Mr. Czubernat leans into more in the future.

John began collecting watches in 2018, when he realized that the hobby meshed well with his love of studying history and researching obscure topics. In addition to watches, John enjoys collecting fountain pens, learning languages, reading, and traveling.