Russian Watches Part 1: Pre-Revolution Russian Clockworks (Huge Swinging Clocks!)

By: Kaz Mirza

Although it probably wasn’t apparent at the time, watches and clocks were destined to change forever on the night of November 17th, 1917. This was the date that the Russian working class people opted by force to set themselves on the course to partake in the large scale social experiment called Communism. Now most articles that discuss Russian watches and timepieces will begin discussing watchworks crafted after this date, which, to me, is craziness.

It’s not my intention to downplay the impact communism had on Russian watches. Rather, I feel that the true aficionado (of which most true watch collectors will consider themselves) aims to understand the full context of any significant event that piques their interest or passion – i.e. the impetus behind those defining moments. That is to say, specifically here, an introduction to pre-revolutionary (pre-communist) watches and clocks. To focus only on watches created during the soviet union implies that Russian watch history simply decided to sprout from the earth one day full grown – from the womb to puberty. That’s obviously not the case – Russia has been producing clockworks and watches for centuries almost on par and in the same timeframe as the rest of Western Europe (to certain technological extents, that is).

So what follows is kind of a timeline/historical breakdown of Russia’s relationship with timepieces and how they were shaped by time and perceived by its population up to the formation of the Soviet Union.

1400-1600 AD: Modest Monastic Timekeeping

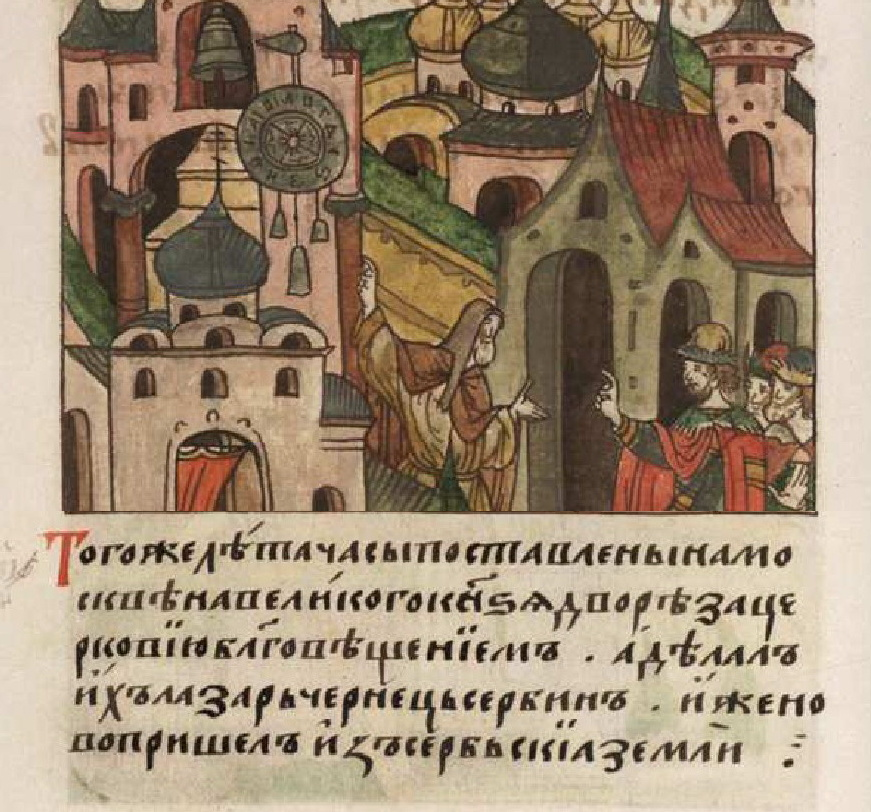

Some of the earliest accounts of clockworks and horology innovations are very similar to those seen across Europe: monastic timekeeping. Numerous accounts corroborate that a Serbian monk named Lazar the Serb (sometimes you’ll see it as Lazar Serbin) created the first mechanical clock mechanism in Moscow after he was displaced from Serbia to Russia by Ottoman invaders.

Roughly 100 years later clock towers (also inclusive of bell towers/striking towers) were a common site among monasteries and fortresses across Russia. The reality of their inclusion in these fixtures is evidence that everyday public life relied on the different striking mechanisms of the towers. These chimes or bells would have dictated the everyday flow of life in terms of agriculture, social gatherings, religion, and more. One noteworthy clock tower worth mentioning would have been found on the popular Solovetsky Monastery. Solovetsky is located in the northern region of the Russian state and would have been considered remote – as a result, self-reliance was crucial (as was the case with most monasteries). But because of its location and other factors, it was considered a politically powerful force within the Russian Orthodox Movement at the time. Evidence seems to suggest that in 1539 a clock tower was built on the monastery grounds as a possible result of the location’s physical and spiritual importance. The mechanism chimed quarter hours, half hours, as well as separate day and night hours (which would have been useful since the region most likely experienced a longer than normal duration of daylight and night due to its proximity to the North pole).

1600s AD: aka “Holy Shit Everyone’s Dying!”:

Ok, so here’s where it starts to get weird for Russia (and incidentally its attitude towards clockworks). From about 1598 to 1613 Russia experienced what was later called the “Time of Troubles,” which is an astronomical understatement on the same level as being decapitated and calling it “a bad day.” The most noteworthy event that occurred was when ⅓ of Russia’s population died due to starvation – that’s about 2 million people and they died within 2 years.

During the Time of Troubles, Russia experienced political turmoil, social/economic devastation, as well as repeated military losses and failed invasion attempts. Now it’s not fair to try and reduce the study of Russian economics and politics to an absolute facet or statement; however, despite all the crap the country had endured (mostly self-inflicted) the state has always had two things going for it: people and an insatiable need to conquer and occupy.

So despite the numerous impediments that the Time of Troubles placed on the Russian state, increased European relations always meant that war, skirmishes, and opportunity for new land grabs were always on the table for the Tsarist regime. But war and all that fun stuff is expensive, so how do they finance a military while running a dying country? If you guessed “tax their huge population into financial nothingness during the worst financial and social period in their history,” then you’re right! They taxed the hell out of the population to fund increased military efforts.

But to add insult to injury, while the everyday working person in Russia was experiencing hell, the Russian nobles and aristocrats were basically living it up. They had parties and partook in large displays of opulence while people starved to death on the streets as a result of their government’s failure.

So why bring up famine and increased Russian opulence in a discussion about Russian watches? Because attitudes towards clockworks in Russia followed the same trajectory seen in other parts of Europe – clocks and timepieces became status symbols. In the 1600s Moscow saw an increase in specialized goldsmiths and craftsmen who specifically served noble/aristocratic horology needs. Clockworks were getting more decorated, intricate, and (inevitably) more expensive.

However, in other parts of Europe were these horological attitudes were changing, the everyday population was also experiencing the Renaissance (ca 1300-1600s). Not to get super sidetracked, but with the Renaissance came new attitudes towards art, culture, and most important, trade/mercantilism. Increased trade meant that wealth wasn’t only reserved for those born noble – potentially everyone had a better opportunity than before to earn wealth. In essence, the Renaissance signaled the rise of the middle class that would later come to fruition in the Western world.

This meant that the budding middle class in Europe had the opportunity to afford things traditionally only reserved for noblemen and aristocrats. However, just so we’re clear, Russia did NOT experience anything resembling a Renaissance on the same level as the rest of Western Europe. Remember the Time of Troubles where people were starving to death? Yeah, Russia was going through that during the European Renaissance. So the events that precipitated a budding middle class in Europe didn’t take place in Russia, which means the divide between poor and noble was very clear without any blur. So basically what I’m getting at is that Russian clockworks (just like the rest of Europe) got more expensive; however, it’s population (unlike the rest of Europe) got even poorer. So a timepiece in Russia became an even stronger status symbol than it would have in the rest of Europe.

1700 – 1800s AD: The Broken Economy Takes Its Toll:

The wealth and social divide between the everyday common person and the noble/aristocratic class grew even greater during this time period. At the same time, even though timepieces and clockworks were only available to the rich, horology grew very sophisticated and enjoyed a lot of reverence from both Russian aristocracy and the Tsars. During the 1700s watches and clocks were commonly adorned with bronze and gilded designs in order to mainly serve as desk and mantelpiece ornaments for the rich. In addition to this increase in ornamental style, timepieces also became very intricate. I suspect, very similar to today, that intricate timepieces often served as conversation pieces between the very wealthy (“Well, you know, this watch I paid $200,000 for has TWO flying tourbillions…”).

However, these advancement in luxury craftsmanship pieces were extremely disproportionate to advancements made in agricultural and industrial growth – especially in relation to the relative advancements of other European counterparts. Russia’s chronic inability to industrialize and coordinate the agricultural practices of its extremely large population only served to worsen the situation and increase poverty. Plus, adding insult to injury, Russia for many years was a serfdom, a system of feudal oppression where serfs were essentially allowed to occupy land owned by a landowner, but only if they (the serfs) worked the land for the landowner (who basically got all the profits from their work). In essence, and to spare you a very detailed explanation, it was a form of slavery. Serfs had an obligation to their landowners and the owners had an obligation to them (offering them shelter and protection), but the system was corrupt. Landowners essentially owned the serfs and all of their property. Serfdom was supported by the head Russian government for centuries, which resulted in generations of landowners relying on serfs to work the land and maintain their estates.

Well, in 1861 Serfs were emancipated and granted freedom, and as part of the emancipation they were granted the opportunity to buy land, which many of them did. Now this sounds great but keep in mind that the serfs couldn’t own property and didn’t earn a wage before emancipation. So when it came time to buy land they had no savings or collateral. So the state offered them 100% mortgages with no money down. Now, again, that sounds nice, but when it came time to pay their fees for taking out these mortgages, the serfs couldn’t afford it. Adding insult to injury, you now also had an innumerable amount of legacy estates, who for centuries relied on serfs, completely serfless. That’s a serious issue because the landowners had no idea how to maintain the land. So many of these estates fell into disrepair and landowners fell into debt.

So Russia not only had a technologically stunted agricultural and industrial infrastructure, it had a lot of people who were failed by the system now crippled by debt and left with useless land.

While the government should have been focusing on these issues and the preceding factors behind them, want to know what they were focusing on instead? Parties. Lots of parties and gift-exchanges between other nobles. Commonly, watches and clockworks were one form of gift often exchanged between these people. So while all these rich asshats are powdering their noses and exchanging gold covered mantle clocks, people were dying with empty stomachs and broken spirits – utterly failed and disregarded by a government that deprioritized them.

Interested in some context on how skewed the Tsarist government’s perspective was? In the late 1700s Catherine II felt that the Russian state needed to focus more on creating clockworks and timepieces in order to better compete with European counterparts and elevate certain aspects of high society in Russia. So she commissioned and oversaw the creation of two specialized workshops in Moscow and St. Petersburg that focused on creating very ornate timepieces and clocks. These items were designed to be used in stage coaches but mainly served as honorary rewards for those who served the government well and for special events. The construction of these facilities and the opulent priorities of the Russian aristocracy would have been very visible and very clear to the everyday working person who was suffering. I guess it was more important to decorate pretty clocks that only a small portion of the population could afford rather than improving the country’s infrastructure and agricultural practices? Priorities, people – priorities.

Early 1900s – The October Revolution

In 1917 the Tsarist government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks (the event later called the October Revolution). Basically, this was the response to the years of poverty forced upon the everyday Russian citizen as a result of the opulence enjoyed by the Tsars and aristocracy. The Bolshevik’s perceived (and rightly so) that the upper class’ focus on wealth, opulence, and superfluous luxury goods crippled the country’s economic potential and stunted their growth as an industrial nation.

After taking over and taking a step back from global relations for a period of time. Russia had to essentially set up a functioning system of government from the ground up where economy, social equality, and self-reliance was prioritized. Different departments were set up to handle different aspects of government the new ruling party felt were important. One of these departments was The State Trust of Precision Mechanics established in the early 1920s. All those smaller horology enterprises that mainly serviced the upper class aristocrats before the revolution basically went under this department’s control. Under The State Trust of Precision Mechanics these small watch making operations basically continued doing what they were doing until they ran out of existing materials they had acquired before the revolution. Once they were out of materials is when things got interesting.

Before Communism, all the parts and machinery Russian watch technicians were using were from outside the country. What was very popular actually was importing all the separate parts to build a watch from Switzerland and assembling them on Russian soil. This was popular because it helped the Russians avoid import taxes. But as far as the new Communist government was concerned, this reliance on external resources was indicative of what they perceived to be the economic sickness of Tsarist Russia – the inability to industrialize and to rely on themselves as a nation to provide what they needed to grow. They recognized that bringing in these parts from the Swiss wasn’t sustainable for the Russian people. So when the few small(ish) watch operations in Russia ran out of Swiss parts, the Russian government reached a conclusion. It’s time to build a watch factory where we can do everything in-house. A place where every component for a watch could be created. But more than that, a factory that will make watches for technical purposes, for awards, but, most importantly, for the general Russian person (man, woman, and child). A watch factory on Russian soil would mean that horology would no longer reserved the for the ultra-rich or noble born. The new Russian government believed in equal share for all. This was the dream that precipitated the creation of the First Moscow Watch Factory.

Read on to Russian Watches Part 2: The First Moscow Watch Factory (PolJot)

Co-Founder and Senior Editor

Kaz has been collecting watches since 2015, but he’s been fascinated by product design, the Collector’s psychology, and brand marketing his whole life. While sharing the same strong fondness for all things horologically-affordable as Mike (his TBWS partner in crime), Kaz’s collection niche is also focused on vintage Soviet watches as well as watches that feature a unique, but well-designed quirk or visual hook.

Really enjoying this series, Kaz. Can’t wait to read the rest of it.

Holy crap – can’t believe someone is actually reading these lol – I was so worried they’d be boring as hell since they’re super niche. But I’m glad you’re digging them – as always, super open to critiques as you read on, man. I’m always looking to shape this series up. Working on the Vostok one now and I’d like to include a proper conclusion on the Poljot piece.

My grandfather lived in Crimea in the 1920’s. His father died while on a train and a man returned his pocketwatch to my grandfather. What might this watch have been like? They were farmers on the Crimean peninsula.

Hi, Ann:

It’s difficult to say since most of the watches that were circulating before the creation of the First Moscow Watch Factory were sourced from many different places. However, given the potential time period it’s most likely that the watch was of Swiss origin, either assembled outside of Switzerland or made in Switzerland and then removed from the country after purchasing. I’m sharing a couple links to other pre-Revolution pocket watches that feature the simple design that your great grandfather’s watch most likely had. Again, it’s difficult to pinpoint specifically any more concrete details, but I hope this info and these images are of assistance.

https://www.ussrtime.info/details/0971.html

https://www.ussrtime.info/details/0691.html

Best,

-Kaz

Great summary of Russian history. Cant wait to see what happens next. Your writing style makes what could be a very dry subject come to life. Looking forward to the next episode. Loving the podcast by the way.

Hey, dude! Super happy you’re enjoying the series and thank you for the kind words! Honestly this stuff is just super fun for me so I guess it usually shows when I write about it lol. Going to start working on the Raketa portion next – keep an eye out for that!

Hi Kaz,

And it’s still being read!

I just bought my first russian watch, a poljot alarm, and it has sparked something.

I’m glad I found your readings on this beautiful niche. Thanks a lot!