In watch culture today, “tool watches” are those meant for physical activity; the gym, swimming, scaling Mount Everest, setting new freediving records – you know, the things we all do, all the time. In reality, every watch is a tool, regardless of its water resistance rating or its ability to survive a drop from a three-story building. Organizing human activity is a major logistical challenge, and many require timing and coordination, though the degree to which that’s true varies. Timing military operations to achieve maximum pressure on the objective needs a little bit more coordination than meeting with some friends for lunch across town (though that may depend on the friend group).

As I mentioned in my last article on my Atelier Wen, I believe that when people scoff at Chinese watches, they’re thinking about them from a luxury standpoint. They look at heritage, prestige and brand longevity, rather than the original intent of the founders of China’s watchmaking industry in the first place. In this article, I want to introduce you to the Shanghai Watch Company, one of the oldest watch companies in China, and once known as “China’s Rolex.” A lot of watch design these days is inspired by watches of the mid-20th century. Beyond the outright reissues, you see all manner of brands taking inspiration from the skin divers, GMTs, and chronographs of the 1950s and 60s. It’s when Rolex released the Submariner, Longines developed its Conquest line, and Omega’s Constellation series won its accuracy awards.

Things were going drastically different in China in the same time period. The Second World War, followed by a civil war between the Communists and the Nationalists, left much of the country in ruins by the time the Communist Party took power in October of 1949. Even prior to those conflicts, China did not have a domestic watchmaking industry. Individuals were able to repair watches but lacked the manufacturing capacity to produce them on their own. As part of the greater effort to develop industry, in 1955 the central government gathered watchmakers from across the country to develop a watch for domestic production. The original group tasked to develop the watch industry in Shanghai consisted of just 58 people, and would eventually be renamed as the Shanghai Watch Company. This group of watchmakers worked in tandem with several others, one of which would be known today as the Seagull Watch Company.

Because of the desirability of watch and its expense (it was consistently one of the most expensive brands among domestically produced watches), Shanghai gained a reputation as the “Rolex of China.” Beginning in the sixties, there was a common saying that before a man could get married, he needed “four big things” (四大件;sì dàjiàn): a bicycle, a radio, a sewing machine, and a watch. These were considered status symbols, as having all four established one as a man of means, in a country whose economy was just developing. From the late 1950s until the 1980s, the watch that was most coveted of all was a Shanghai.

Through the development of watchmaking in China, the government opened dozens of factories across the country. Many had their own movements, which varied in quality. Typically, they were named after the province or some terrain feature in the area. Watches like Zhongshan had low-jewel, less accurate movements, but tried to make up for it with interesting dial patterns.

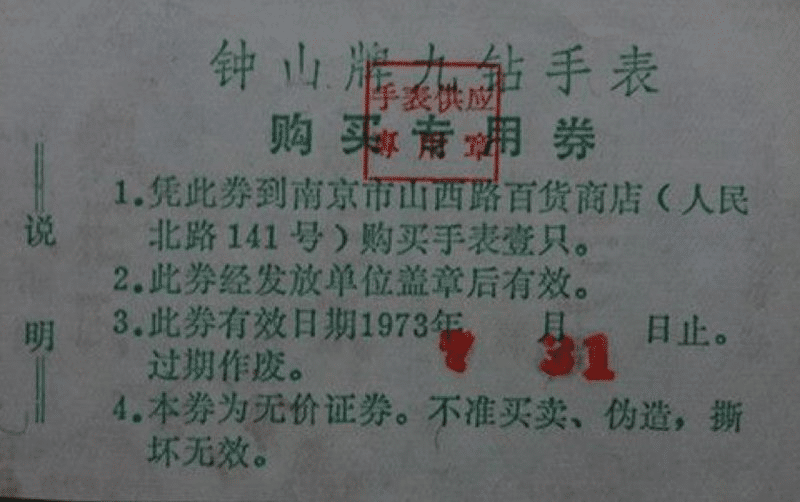

Shanghai watches, though, were considered a top-tier brand. Excellent quality, high-accuracy movements, and notoriety at the first watch brand that the country developed led to a significant leap in prestige over other brands, even in a country attempting to make every aspect of life more egalitarian. At the time, it cost as much as several months’ pay, hence the nickname “China’s Rolex.” Moreover, because there were never enough watches in stock, a person required a ration card for that specific watch, resulting in long wait lists. Though, at least for these watches, that scarcity wasn’t artificially induced!

The Shanghai Watch Company developed several watches known to collectors today as the He Ping and Xima watches, but these were not mass produced. The first watch meant for mass production was released in 1958, named the A581. The Shanghai Watch Company made just 13,600 of the A581 in its first year of production, well short of satisfying demand across the country. The A581 was followed by the A611 and a series of variants, the most famous of which was the A623. This model, which was the first to have a date complication, was worn by the first premier of China, Zhou En-Lai.

Shanghai went on to develop several more watch models, to include the 1120, 1523, and 1524, all of which used the Shanghai developed SS1 movements, running at either 18,000 bph, or the SS1A-K (“K” standing for 快;kuài – fast), which ran at 21,600 bph. In the 1970s, however, the central government made the decision to standardize all movements across all of the watch factories in the country. All watches would now use the “unified movement” – the tǒngjī (统机), though there were several notable exceptions, whose movements greatly surpassed the standards of the tongji. Shanghai’s following model, the 7120, and all following models would use variations of this movement. Shanghai made millions of the 7120, making it one of the most recognizable Chinese watches of the 20th century.

Shanghai was responsible for producing several watches for the People’s Liberation Army. Beginning in the 1970s, the government tasked Shanghai to create a dive watch for its military, as they did not want to rely on foreign companies for any capability they themselves could produce. The company developed two watches, the SS2 and the SS4. The SS2 was a 29- jewel automatic movement, and the SS4 was a 24-jewel automatic movement. However, the cost was so high that only the highest-ranking PLA officers could afford them. SS2s were offered for sale to general officers, and SS4s were offered for sale to regimental commanders.

At the time, Western intelligence agencies had very little understanding of the Chinese watch industry, as they had few to no contacts inside the country. A recently-released report by the CIA on the Chinese watch industry had only anecdotal evidence of their capabilities, with its only point of data being a watch that a Taiwanese officer purchased while he was given a tour of the factory; he stated that it ran better than his foreign-made watch, though the brand was not specified. Any watches not purchased were eventually collected by the state and destroyed, similar to the Tornek-Rayville watches used by the U.S. military in Vietnam.

There were several Chinese watch brands that fell under the Shanghai factory. The most notable of these was the Zuanshi (钻石), or Diamond, brand. This factory eventually developed the SM1A-K movement, which won the Chinese competition for “most accurate wristwatch” nearly ten times through the course of the 1970s.

Beginning in the 1980s, the Shanghai Watch Company experienced a period of significant decline. As the domestic market began to open to foreign brands, Shanghai and other domestic companies were no longer seen as status symbols. People sought to purchase actual Rolexes, among other watches that were newly available. At the same time, quartz watches provided cheaper alternatives to traditional watches. Shanghai shrank to a fraction of its former self, though it did not disappear entirely.

Today, the Shanghai Watch Company is still producing watches. However, its new lineup is significantly different from its former offerings. It includes watches featuring artisanal dials, unique dials that rotate once every hour, and watches where the balance wheel is featured prominently above the dial. Shanghai has also created a heritage line, producing watches inspired by its older designs. The heritage line consists of a series of homages to both the 7120 and A581 models, in 39mm and 31mm sizes. Shanghai manufactures several of its own movements, but for its simpler models such as the 3-hand reissues it uses Seagull movements.

If you are interested in Chinese horology or Chinese history, vintage Shanghai watches are regularly available on Ebay, though it should be said that like anything on Ebay, caveat emptor. Most often available are the later models, such as the 1120, 1523/1524, and the 7120. There are, however, rarer models you are unlikely to find on Western platforms. Models such as the SS2/SS4 military watches, A623s, and very early A581 examples are all highly sought after collector’s items, and won’t be easily available. Many often go for thousands of dollars!

I have seen multiple YouTube videos in the last year or two that are reviews of “Shanghai” watches, which appear to be 7120s that they purchased on Alibaba. These are not Shanghai watches. At a minimum, they are frankenwatches, put together decades later from original Shanghai parts. At worst, they’re likely outright fakes, which can be easily sold at low prices in high volumes. If you’d like a vintage piece, I recommend checking out NeoBiao; if you would like a newer model, check China Watch Shop for information on stock numbers and links to buy them from.

I’m not here to try to convince you to buy a Chinese watch; there’s no such thing as “you NEED to own this to be a true collector.” I’m only writing this to share a piece of history that I don’t think many people know about. The domestic Chinese watch industry ultimately achieved its goal of producing reliable, accurate watches for its population, at a scale that dwarfs that of any other watchmaking nation. China continues to produce a quarter of the world’s watch movements. While they may not be as prestigious as they once were in their country of origin, Shanghai watches are an important symbol of the history of China’s development as a modern industrial nation, and the manufacturing giant it is today.

John began collecting watches in 2018, when he realized that the hobby meshed well with his love of studying history and researching obscure topics. In addition to watches, John enjoys collecting fountain pens, learning languages, reading, and traveling.